|

Group A Streptococcus (GAS), more commonly known as Strep A, is usually found on the skin or throat. It is most prevalent among children aged 5-15 years and adults who are parents of school-aged children are an increased risk group of Strep A. According to The Sun, “there have been over 40 children reported to have died from Strep A in the UK as the deadly infection grows.” In PharmAlliance, we would like to explore causes, prevalence, symptoms and treatment of Strep A in this blog to inform and bring attention to this “deadly infection” to stop its asymptomatic threats from causing more deaths among the younger population. GAS is a type of bacteria that can cause a variety of infections. Strep A infections are highly contagious and are most commonly spread through close contact with an infected person through respiratory droplets or through direct contact with infected skin sores. The symptoms of a Strep A infection can include: flu-like symptoms such as high temperature, swollen glands or an aching body, sore throat, a rash that feels rough, scabs and sores, pain and swelling, severe muscle aches and nausea and vomiting. As of December 2022, there has been an increase in the incidence of strep A in the UK, which has resulted in the NHS experiencing significant pressures, especially during the period where pharmacies were faced with shortages of antibiotics. There have been several theories illustrating potential explanations for the increases in strep A cases. It has been thought that recent increases in strep A cases may be related to the early spikes in influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infections, along with the continued spread of COVID-19. This has eventually led to colonization and infection of Strep A bacteria. Strep A infections are also more likely following chickenpox – another viral infection. Another possible theory is that the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in decreased exposure to strep A infections during lockdown. Hence, a greater number of individuals were prone to this infectious disease as a result of reduced immunity levels. Most cases of strep A are mild and can easily be treated with a course of antibiotics. Strep A generally has non-invasive manifestations such as pharyngitis (sore throat), impetigo and scarlet fever. If the patient is suffering from a sore throat only, the first line treatment in this case is phenoxymethylpenicillin for 5 days or if the disease has progressed to scarlet fever this treatment should be increased to a 10 day period. Phenoxymethylpenicillin is also indicated in the prophylaxis of iGAS (invasive group A streptococcal disease) which occurs when the bacteria spreads to the lungs, bloodstream and in turn other parts of the body. This leads to invasive diseases such as bacteraemia (streptococcal bacteria in the bloodstream), necrotising fasciitis (also known as “flesh eating disease”, as damage is caused to soft tissue) and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (toxins being released into the body by streptococcal bacteria). In these cases it is essential the patient is treated with IV antibiotics as there is a risk of sepsis or even death. There is no vaccine to protect against strep A. It is important that after a diagnosis of iGAS, close contacts are identified. A close contact is anyone who has “had prolonged contact with the case in a household-type setting during the 7 days before onset of symptoms and up to 24 hours after initiation of appropriate antimicrobial therapy”. High risk contacts such as the elderly and women who are over 37 weeks pregnant should be offered prophylactic antibiotic treatment as soon as possible. If the patient is allergic to penicillin, it may be substituted for clarithromycin. In cases of phenoxymethylpenicillin shortage, amoxicillin, macrolides, flucloxacillin, cefalexin and co-amoxiclav can also be offered. In summary, it is important for us to spot warning signs of Strep A infections among individuals with elevated risks of infections. Common symptoms include fevers, white sores in the throat and sore throat that lasts more than 5 days. We have discussed multiple antibiotic treatment options available above for both mild and severe infections but prevention is always better than cure, especially in the winter when the incidence rate is high. Personal hygiene measures, such as frequent hand washing with soap and water, covering one’s face while coughing and sneezing and avoiding contact with people infected with Strep A infections, can greatly reduce the possibility of infections as Strep A is transmitted through respiratory droplets and skin contact. Written by Peony, Ubaid, Supeedsana, Mumtaj and Alex References https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/invasive-group-a-streptococcal-disease-managing-community-contacts https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/group-a-streptococcus-communications-to-clinicians/ https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/infections-and-poisoning/streptococcus-a-strep-a https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/strep-a/ https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/strep-throat/symptoms-causes/syc-20350338#:~:text=Strep%20throat%20is%20caused%20by,through%20shared%20food%20or%20drinks. https://www.gavi.org/vaccineswork/whats-behind-recent-surge-strep-and-scarlet-fever https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2022-DON429 https://www.thesun.co.uk/health/21100770/children-died-strep-uk-cases-infection-grow/

0 Comments

STI stands for sexually transmitted infections which are generally acquired by sexual contact. The bacteria, viruses or parasites that cause sexually transmitted diseases may pass from person to person in blood, semen or vaginal and other bodily fluids. Many sexually transmitted infections do not have any symptoms and can be passed from person to person unknowingly. This makes education regarding safe-sex practices and what symptoms to look out for should they occur a key factor in preventing STIs and treating them before they develop into more serious conditions. As pharmacists, STIs are some of the most common conditions that you will come across in practice and pharmacies will often provide several essential services in order to improve sexual and reproductive health, particularly towards vulnerable groups - those most likely at risk of catching them. We will be discussing some of the most common sexually transmitted infections and their symptoms, the reasons why there is still an increasing number of young people catching STIs and the services that pharmacies can provide in order to improve education on prevention and treatment.

Some examples of STIs are:

The most common STI in the UK is chlamydia as stated by the NHS. Chlamydia is easily passed on during sexual intercourse and most people don’t experience any symptoms, so they’re unaware that they’re infected. Over the coming years there has been a rise in the number of STI cases in the UK being diagnosed. Doctors and sexual health clinics diagnosed 447,694 new cases of STIs in 2018 which was 5% more cases compared to the previous year. Lack of public awareness and training about STIs, discomfort with discussing sexual health issues, increasing numbers of young people associated with opioid misuse and adverse childhood experiences (neglect, confinement, household substance abuse) remain as issues faced by young people. To overcome these barriers, prevention can be achieved through sex education programmes (campaigns, access to reliable contraception and services) by informing about abstinence, use of condoms etc. to reduce rates of sexual activity and risk behaviours. The increase in new cases of STIs is due to lack of sexual education across the UK. It is with this lack of education on how to have safe sexual intercourse that increase the frequency of cases of STIs. Another factor is that young people tend to feel uncomfortable talking about these topics as they are quite sensitive and young people may not be ready to discuss such topics hence do not attend such education. Pharmacists’ potential to support sexual health in young people and adolescents, ranges from providing STI screening and ensuring patients adhere to treatment for the most effective outcomes, to educating more younger generations on signs and types of illnesses. There has been a shift in the involvement of pharmacists towards sexual and reproductive well-being in young people such as offering contraceptives and safe sexual practices in primary care or clinics. According to Oxford Academic, “confirming possible underlying factors leading to this pattern of behaviour, such as perception of less risk of stigma by going to the pharmacy, lower treatment cost at the pharmacy…” [Chin, 2011]. This highlights several advantages of training qualified and newly qualified pharmacists to be knowledgeable in the variety and differentiation of sexually transmitted diseases. To conclude, we found that STIs are one of the most prominent issues we face in communities, especially as pharmacists. We should pay particular attention to patients who develop symptoms that may resemble STIs and to be confident in approaching them. We acknowledge the difficulties we may encounter while we communicate with these patients but by having empathy towards such patients, and focusing on improving their health rather than stigmatising them we will be able to tackle STIs as a team. We should continue in championing public education of safe-sex practices and the symptoms to look out for to raise the awareness of STIs in the communities. Written by Mumtaj, Ubaid, Supeedsana, Peony and Alex References: https://www.132healthwise.com/how-common-are-stis-in-the-uk.php https://www.letstalkaboutit.nhs.uk/worried-about-stis/information-about-common-stis/#:~:text=Chlamydia%20is%20the%20most%20common,are%20unaware%20they're%20infected. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sexually-transmitted-diseases-stds/symptoms-causes/syc-20351240#:~:text=Sexually%20transmitted%20diseases%20(STDs)%20%E2%80%94,vaginal%20and%20other%20bodily%20fluids. https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/public-health-now/news/why-are-so-many-teens-getting-stds https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pharmacy-offer-for-sexual-health-reproductive-health-and-hiv Chin.K (2011): sexual/reproductive health and the pharmacist: what is known and what is needed? Available at: https://academic.oup.com/jphsr/article/2/2/65/6087447 [Accessed on 16th December 2022] When you think back to the beginnings of the Thanksgiving holiday in the United States, many Americans are familiar with the Pilgrims’ arrival in New England. These English settlers formed a settlement in Plymouth, Massachusetts, and later celebrated a good harvest with the Wampanoag people who had helped them through the previous year’s winter when food was scarce (1). By the early 1800s, it was customary to celebrate Thanksgiving on the last Thursday of November, and this was made official by Abraham Lincoln in 1863 (2). Did you know that in 1939, Franklin D. Roosevelt moved the holiday up by a week in order to help increase sales for the Christmas season? This practice didn’t last very long because in 1941, he signed a bill to officially change the date of the national holiday to the fourth Thursday in November (3). Although this holiday has history rooted in religion, it is now a secular holiday widely celebrated across the U.S.

The U.S. isn’t the only country that celebrates Thanksgiving. Other countries have their own versions of Thanksgiving or harvest celebrations occurring between October and November. In Canada, Thanksgiving is celebrated on the second Monday in October and many Canadians get that day off to enjoy the holiday over an extended weekend. In the Philippines, Thanksgiving is celebrated on the same day as in the U.S. and is part of a long Christmas season. Black Friday in the U.S. occurs the day after Thanksgiving and marks the beginning of the Christmas shopping season. However, many businesses in the Philippines start having sales for Christmas as early as September. In Japan, Labor Thanksgiving Day falls on November 23, and celebrates labor and production on top of giving each other thanks (2). These are just a number of countries that recognize the observance of Thanksgiving. In terms of foods eaten during American Thanksgiving, the turkey has become synonymous with the holiday and is often the centerpiece of a traditional Thanksgiving meal. Second to turkey, baked ham is also a popular main dish served. Common traditional sides include mashed potatoes, stuffing, and cranberry sauce, and a pie such as pumpkin pie is usually served for dessert (4). Of course, there are many other sides and desserts that can be seen depending on regional or cultural differences. In the south, you may also see things like green bean casserole, mac and cheese, collard greens, and sweet potato pie. What dish/side is your favorite, or which would you be most excited to try? (Personally, I'm a big fan of stuffing and mashed potatoes!) In addition to gathering and eating together, families can tune in to watch thanksgiving day parades. The parades usually run for about 3 hours and some notable ones include the 6abc Dunkin’ Thanksgiving Day parade, which is the oldest Thanksgiving parade in the US; the America’s Thanksgiving Parade; and, arguably the best known, the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade in New York City (5,6,7). In the Macy’s Parade, some familiar and crowd favorite balloons are Snoopy, Pikachu, Mickey Mouse, and Garfield. All the balloons are made by the Macy’s Parade Studio, and companies can pay each year to have their balloon featured in the lineup (8,9). If you’re interested in seeing some of the fun characters in this year’s lineup, take a look at https://www.macys.com/social/parade/lineup/ To all those celebrating, have a Happy Thanksgiving and enjoy the break with your friends and family! Written by: Natalie Ly References: (1) Wikipedia contributors. Plymouth, Massachusetts. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Published November 5, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Plymouth,_Massachusetts&oldid=1120213209 (2) Wikipedia contributors. Thanksgiving. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Published November 19, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Thanksgiving&oldid=1122815048 (3) Silverman DJ. Thanksgiving Day. In: Encyclopedia Britannica. ; 2022. (4) Wikipedia contributors. Thanksgiving dinner. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Published November 9, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Thanksgiving_dinner&oldid=1120939697 (5) Wikipedia contributors. 6abc Dunkin’ Donuts Thanksgiving Day Parade. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Published November 19, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=6abc_Dunkin%27_Donuts_Thanksgiving_Day_Parade&oldid=1122701256 (6) Wikipedia contributors. America’s Thanksgiving Parade. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Published January 28, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=America%27s_Thanksgiving_Parade&oldid=1068492956 (7) Wikipedia contributors. Macy’s thanksgiving day parade. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Published November 21, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Macy%27s_Thanksgiving_Day_Parade&oldid=1122995147 (8) Neary KS. Ultimate guide to the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. HowStuffWorks. Published November 17, 2019. Accessed November 21, 2022. https://people.howstuffworks.com/culture-traditions/holidays-other/macys-thanksgiving-day-parade2.htm (9) Conradt S. How are balloons chosen for the Macy’s thanksgiving day parade? Mental Floss. Published November 19, 2018. Accessed November 21, 2022. https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/29284/how-are-balloons-chosen-macys-thanksgiving-day-parade (and how to get them)1. Attention to detail

This should be a no-brainer. You are working with medications that will ultimately affect real-life patients, so there is zero room for error. Pharmacotherapy accuracy is crucial, but one area that many students forget to master is compliance knowledge. Understanding GMP (Good Manufacturing Practice) regulations are important in ensuring high quality standards are met and that companies are following health and safety requirements. On average, a non-compliant company must pay a $9.6 million penalty. Luckily, most pharmacy programs incorporate legal regulations as part of the curriculum, so PAY ATTENTION. You can also get a GMP certification to help distinguish yourself from the crowd and demonstrate your understanding of industry best practices. 2. Problem Solving Strategic thinking is essential in any industry, and the same holds true in the pharmaceutical realm. You will be working on complex projects that require constant innovation and planning ahead. Work on that procrastination problem while you’re still in school, because time-management will only get harder in the real world. Employees who are quick to problem solve are valued heavily in the industry. The best way to improve critical thinking is to put yourself in scenarios that require it (i.e. leadership positions in clubs). 3. Interpersonal Skills Communication is key! You may be used to working by yourself in an academic environment, but it’s all about collaboration in an industrial environment. You must be able to quickly and concisely convey complex scientific information in layman’s term. Talking is great, but it’s also crucial that you can empathetically listen to others. Hone in on your emotional intelligence skills and make sure to always ask intelligent follow-up questions. 4. Growth Mindset Learning doesn’t stop once you leave the classroom; in fact, I would argue that it becomes more prevalent post-doctorate. There is no longer an overhead authority figure to ensure you are learning and passing. It becomes up to you to stay up to date on the latest therapies and industry trends. The best way to do this is to read pharmacy related news articles daily. Here are a few recommended sources: https://www.fiercepharma.com/, https://www.biopharmadive.com/, https://www.morningbrew.com/daily 5. NETWORKING I cannot emphasize this enough. NETWORK, NETWORK, NETWORK. All your perfect grades, publications, and leadership roles mean nothing if you can’t land a job. Talk to professors after class, reach out to like-minded individuals, attend conferences…. There are a plethora of ways to network. If you prefer not to leave the comfort of your home, hop on linked-in and start messaging away. Don’t be afraid to reach out to people with your dream job and set up a 20 minute coffee chat. People, especially recent graduates, are eager to share their knowledge and experience. Written by: Gautham Venkatesh The middle region of the state of North Carolina is known around the world for being a science and technology hub known as the Research Triangle. The tips of this “triangle” are three well-renowned universities: the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in Chapel Hill, Duke University in Durham, and North Carolina State University in Raleigh. The proximity of these three universities to one another has allowed the area to grow into the perfect location for young adults and students to live in, but besides going to classes and studying, what is there to do in Chapel Hill?

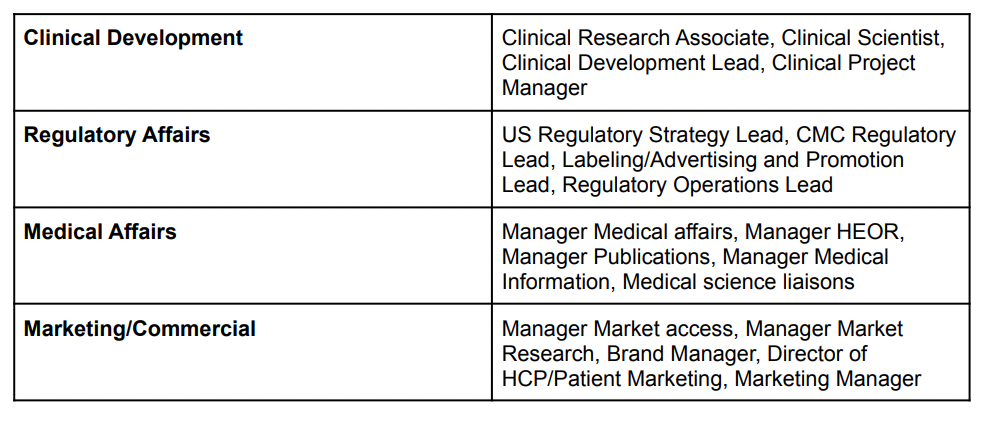

Chapel Hill is home to some iconic places that are recommended for tourists to visit, but long-time residents enjoy visiting as well. To start things off with a place that is somewhat pharmacy related, Suttons Drug Store has been standing on Chapel Hill’s main street, Franklin Street, since 1923, and while the pharmacy is no longer working, it is now home to a diner that serves delicious shakes and burgers for its customers. Another food option also on Franklin Street is Top of the Hill Restaurant and Brewery, which has a great outdoor patio on the top of the building that provides a perfect view of Franklin Street below and is the eighth oldest surviving brewery in the state of North Carolina for those interested in craft brews. In the neighboring town of Carrboro, the Carrboro Farmers’ Market is a must for those who want to purchase fresh produce, as the market includes goods from 75 vendors located within 50 miles and is open every Saturday all year long. Also in Carrboro is Cat’s Cradle, an iconic music venue that has hosted artists like Nirvana and John Mayer and continues to host up-and-coming artists as well as local talents. A bit farther away from downtown Chapel Hill and Carrboro is Maple View Ice Cream & Country Store, which sells award-winning ice cream with classic flavors like chocolate and vanilla, but also flavors that change with the season, and it has a wrap-around porch and large grassy area where individuals can relax and have picnics on (I personally highly recommend this one!). One of the most photographed spots in Chapel Hill is the “Greetings from Chapel Hill” mural that celebrates some of the most iconic landmarks on the UNC campus. The mural was completed in October 2013 by artist Scott Nurkin, and it is found on the back of the building to He’s Not Here, one of the most famous college bars on Franklin Street which is also home to the famous Blue Cup. Another iconic picture spot is the Old Well, a neoclassical rotunda, located in the middle of the UNC campus. In the middle of the Old Well is a drinking fountain that is reported to bring a semester of good luck and a 4.0 GPA to students who drink from it before classes start. I hope you’ve enjoyed this little intro to things to see and do in Chapel Hill! As you can see, there are many places and landmarks to explore in this area and it is always bustling with students and alumni no matter what time of the year. Below is a link for more ideas on what to do in Chapel Hill if you ever visit or if you are just interested in seeing what this beautiful area has to offer: https://www.visitchapelhill.org/things-to-do/ Written by: Emily Relic The Common Misconception “So do you just dispense pills at CVS or Walgreens?” This is a common question that arises from friends and family when the profession of pharmacy is discussed. Many people outside the world of healthcare (and even many within) are oblivious to pharmacists’ vast scope of practice. Over the past 40 years, pharmacists have made significant strides in transforming their public perception from “pill counter” to trusted patient advocate. Pharmacists nowadays contribute regularly to patient care by rounding with medical teams, leading medication adherence efforts, and pursuing federal legislation to reduce drug costs. A novel and growing field is industry pharmacy. What Does an Industry Pharmacist Do? Pharmacists within the industry are employed in a plethora of positions to aid in the drug development process. Practice titles, role descriptions, and skills required vary by company, but the drug development team can be broken down into four categories: Clinical development, regulatory affairs, medical affairs, and commercial/marketing. Examples of positions within each category include: How to get Involved?

It is never too late to consider a career within the industry! If you are a current pharmacy student looking to explore career paths within the pharmaceutical industry, consider joining industry related organizations such as Industry Pharmacists Organization (IPhO) or Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP). IPhO offers an annual VIP Case Competition where students work as a team and compete with other pharmacy schools to construct a comprehensive drug development plan for a fictitious, scenario-based drug. Although proficient pharmaceutical knowledge is crucial, the key to thriving within the industry is NETWORKING. Attend guest lectures and connect with the lecturers to learn about their role within the industry. Other Career Options The role of a pharmacist is no longer reserved to only retail or hospital. Below is a link to the APhA website that outlines various career options available to pharmacists along with a brief description of each: https://aphanet.pharmacist.com/career-option-profiles?is_sso_called=1 Written by: Gautham Venkatesh There are lots of ways to study, some highly effective, others less so. The book How We Learn advocates spacing out study sessions, whereby the same topic is focused on for a short period of time spanned over a few days.¹ It might feel like a bit of a challenge at the beginning, but by gradually re-acquiring knowledge through flashcards and self quizzes one’s learning can become long-lasting.² We have put together the UCL Weebly Blog team’s own accounts of our study methods in this entry. We have covered some ways that have proven to be effective in our studies, such as the Pomodoro time management technique, recording oneself reading aloud lecture notes, actively recalling by answering self-test questions and understanding the context of assignments to actively engage with the learning. We hope this entry can be helpful with your studies, especially as the exam seasons are coming up and we wish you all the best of luck!

I’m Samia: a first-year student in the MPharm degree. As someone who is at the start of my university life, I’ve had to adapt to the various forms of learning that have been exposed to me since starting. One significant change is the structure (or rather, lack of) at university; rather than having a set routine to follow each day, the timetable is constantly changing, meaning that I need to be able to mould my study methods around the different lab classes and workshops that I need to attend. Firstly, before I begin studying - it is important for me to set out my intentions for the day - this could be in the form of a simple to-do list or a more comprehensive schedule. Personally, I like to create a daily time-blocked schedule: this allows me to understand exactly what tasks I need to complete whilst also allowing me to schedule time for my hobbies. The main way in which I study effectively is by constantly implementing the concept of active recall when learning a new concept. Rather than making countless notes, my learning process involves three simple steps - understand, question and recall. Initially, I prioritise trying to completely understand a topic - by engaging with a lecture through annotating the lecture notes - as I go along the lecture slides, I create concise recall questions. Once I have finished studying a topic, I answer the recall questions - thus allowing myself to actively recall whilst also being able to immediately identify the gaps in my knowledge. Although this is my method of learning, the concept of actively recalling a topic can come in many forms and can be personalised to each individual. Furthermore, managing stress and maintaining a healthy work-life balance is crucial to the process of studying. Although these factors are often forgotten about, not prioritising your mental health can lead to ‘burn-out’ and negative mental health. One way that I maintain a healthy work balance is by ensuring that there is a specified time during the week which is purely dedicated to my hobbies - whether that be reading a new book, visiting a new café or going on a walk. As someone who is susceptible to getting ‘burn-out’ from overworking myself, I also prioritise having a consistent healthy sleep schedule, by creating an evening routine - this routine allows me to spend the last few hours of my day in a state of calm by relaxing and therefore, recharging myself for the next day. Overall, I have established that having a study schedule is as vital as maintaining a good balance between study and life, thus allowing a student to prosper whilst being in a positive state of mind. I’m Alex and I’m currently in the second year of the MPharm degree. Learning in the second year involves understanding the fundamental scientific knowledge that underlies common diseases and its application. This application of knowledge is delivered through the chemistry and pharmacy practice modules. My process of learning is to skim through lectures during term time, because most of the time I would be busy dealing with coursework, assignments, laboratory classes and extra-curricular activities; then during the breaks is when I can devote most of the time drilling into topics. One way I find which helps in understanding the factual topics is to read the lecture notes aloud and record myself. It is with reading out loud and involving the two senses of sight and hearing, that I can actively recall what I have learnt from lectures and fill any gaps in my knowledge. Recording myself may seem silly, but it does serve one essential purpose, which is to conveniently pack what I learnt into an easily accessible form. For practical topics, making mistakes is key for me. I allow myself to make mistakes as it helps me to identify my logical flaws and fix any misunderstandings I have about the topics. I am constantly aware of the time involved in this entire learning process and I must admit that I am more than frequently burnt out. I have tried various time management methods but most of them did not work for me. One method which suits me well is to exercise and have entertainment before studying or revising. I then find myself in the mood for studying! I’m Anika, a third year student in the MPharm degree. Being a third year, the most important thing is to be aware of deadlines and managing time efficiently. Not only is this crucial during term time but it is also crucial during the exam season. When preparing for your exams, have a clear structure of what you need to get done. Break this down very clearly into weekly and daily activities to ensure you go through all the material in manageable bitesize chunks. Be as realistic as possible with your daily tasks. I cannot stress this enough - none of us are robots or instant-energy-machines - we cannot possibly focus for a full 24 hours, so be kind. Prioritise the content you struggle with most and more importantly, allocate breaks. One way to do this is through the Pomodoro technique - work for 30 minutes, have a break for 5 minutes, and repeat. Try to get into a good routine, waking up, starting work, having lunch and sleeping at particular times. This helps to motivate and programme your brain to associate certain times of day with particular activities in order to build them into habit. There may be days when you want to sleep in or you struggle to work and that is okay, because whilst it is important to study smart and implement good habits, at the same time it is equally, if not more important to look after yourself as we near exam season. Dedicate time for yourself and build this into your work schedule, whether that be 30 to 60 minutes, or longer, of re-watching your favourite TV series, meeting your friends or continuing that creative project you’ve been meaning to. It is essential, for your wellbeing and to prevent burnout, to focus completely on something you enjoy, besides work. Hope that helps! I’m Sara, and I am currently in my fourth and final year of the MPharm degree. If there was one tip I could share it would be to never give up and to always aim to be your best self, no matter which stage of the course you are at. I noticed that particularly in Year 3, paying attention to the lecturer’s advice and then thinking about what I really wanted to achieve from each assignment helped to put me on the right track. The main difference between fourth year and the previous years of the programme is that this year we are expected to work on most coursework on our own and to use our fundamental knowledge to integrate the different disciplines within pharmacy. We also had the entire Term 1 to spend on our Masters’ research project, so taking responsibility for our work, planning and time management were key. At times, I almost regretted choosing a specific topic for my pharmacology project and some days, identifying the ‘‘right’’ studies and statistical tests to include in the meta-analysis seemed like an insurmountable challenge. However, by asking my supervisor and peers for help and also looking up the concepts or tests I was unsure about allowed me to put everything into context and to exclude information that was likely to confuse the reader. We had experience of writing essays to critically analyse a topic as well as creating and presenting posters mainly from Year 3, so it has been less difficult to approach such tasks for the MPharm research project. On a final note, especially in Years 3 and 4, I suggest that you start early, try and gather as much feedback as you can, take regular breaks, create a rough plan or to-do list daily and/or weekly and lastly, enjoy your time at pharmacy school by joining clubs or societies. That’s all from us! We hope this was useful for you and that you have learnt a thing or two. Exam season is tough but you have gotten this far with your studies so we have no doubt you can get through all your upcoming hurdles too. If you have any study techniques we missed that you’d like to share, then message or tag us at @uclpa on instagram. All the best with your studies! Authors: Alex Ho, Anika Chamba, Samia Hoque and Sara Bashiri. Works Cited:

One of the jewels of the University of North Carolina’s sports club program is a diamond in the rough. The UNC Chapel Hill’s table tennis club is full of elite, top-tier student athletes. The club is run by five highly dedicated officers: Jasper Ou, Elvin Liu, Joseph Ma, Winfield Warren, and Andrew Nguyen. Together, they organize try outs twice a year, four weekly practices, scrimmages, and participate in tournaments from the local to national level.

The club is a part of the Carolina Division of the National Collegiate Table Tennis Association (NCTTA). They compete in the NCTTA divisional and regional tournaments as well as in tournaments outside of the NCTTA, usually held by Triangle Table Tennis Club in Morrisville, North Carolina. In addition to tournaments, just this year the club has participated in two scrimmages: one with North Carolina State University and the University of South Carolina. These scrimmages helped to expand interest in the sport, foster relationships between neighboring clubs and inspire healthy competition. Plans are already going into motion to host two more scrimmages this semester: with Duke University and the University of Georgia. Among the top players in the club is President Jasper Ou from Orlando, Florida who has been playing since the age of 5 and has a rating of 2156. Treasurer Joseph Ma from Cary, North Carolina has been playing since the fourth grade and is rated in the upper 1000s. Vice President Elvin Liu hails from Concord, North Carolina and has been playing for almost two years. The table tennis rating system is similar to chess, with a higher rating generally being more reflective of a greater skill level. In each match, there is an “exchange” in rating points, where the winner goes up and the loser goes down. A rating of 2000 is a recognizably high level of playing skill, while the best in a country are around 2700. A beginner is usually in the 200-1000 range. But the officers aren’t the only players with talent. At the age of 31, post-doctorate student Darius Teo also finds time to play when he is not working on cheminformatics. He’s been playing competitively since the age of 10 back in Singapore, which was actually later than most of his peers. He started playing because his dad and older cousin played at a local club, and he would oftentimes tag along. According to Darius, he joined the UNC Table Tennis Club because he still loves to play and it’s an easy way for him to make friends. Freshman David Nguyen confirms this, saying “My favorite thing about the table tennis club is the mutual respect everyone has for each other. Even though everyone is at different levels of skill, we’re always trying to help each other.” Despite varying backgrounds, ages, and experience, one thing brings these group of students together: their love for the sport of table tennis. For these students, in these uncertain and trying times the club serves as a reprieve from the stress that many of us find ourselves surrounded by. If you’re interested in finding out more about the club and following their progress, their website and Instagram handle are attached below! Website: https://heellife.unc.edu/organization/tabletennisclub Instagram: @unctabletennis Written by: Andrew Nguyen With COVID-19 leaving the world in disarray, the role of the Community and Hospital Pharmacist has grown and adapted vastly to meet the growing physical and emotional needs of the global population, particularly within the healthcare systems of the United Kingdom and United States. By bridging the gap in mental health, providing additional services like COVID-19 vaccinations and screening and sign-posting patients to name only a few services, the Community Pharmacist has been able to serve an integral role of support to the nation, taking the strain off other healthcare professions and providing a key means of accessibility to clinical expertise and advice. It is of utmost importance to note that pharmacists across the globe effortlessly continue to directly care for patients and take on frontline responsibilities amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, yet they are often overlooked when other healthcare professionals are proclaimed⁵. Community pharmacists have effectively reduced the strain on the healthcare system by triaging and screening patients, thus re-routing them away from hospitals⁵. In addition, they respond quickly in other ways to such public health issues, for instance by issuing guidance on professional practice, maintaining the medicines supply chain, handling drug shortages, facilitating the remote provision of pharmacy services, warning against self-medication, taking part in clinical trials and educating on the proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE)⁹. Pharmacists across different sectors have adopted rather different roles during this phase of enormous burden on the healthcare system and resource limitations⁵. Especially in low to middle income regions, community pharmacists provide essential services for free, including ensuring access to telehealth services, dispelling misconceptions and running minor ailments consultations⁵. Hospital pharmacists, on the other hand, evaluate COVID-19 protocols through their presence in ward rounds and antimicrobial stewardship schemes, and also by interpretation of test results and identifying new drug therapies⁵. We have learnt from ‘specialty pharmacists’ how to provide the optimal level of coordination and care to patients remotely, given that they have a long track record of treating patients holistically, and feedback has been remarkably positive from both patients and staff ⁶,¹⁷. Within the UK, a sector of pharmacy which has seen some significant changes is the community pharmacy. Although the ‘pharmacy first’ message has been emphasised and continuously promoted for years, the COVID-19 crisis has led to more patients coming into the pharmacy to treat minor illnesses¹⁷. Additionally, for the majority of patients, the pharmacy acted as their first point of contact, with other healthcare providers, such as GPs being difficult to access, so community pharmacies were presented with more patients, with a wider range of problems¹². Despite the stress that coronavirus has inflicted on society, it has led to pharmacies being more interconnected with other healthcare providers, particularly GPs. Community pharmacists are not only responsible for offering advice and providing treatment, rather they have been adopting a ‘gatekeeper’ role, where they can now cater to a wider variety of patients and refer directly into secondary care¹⁷. Finally, alongside their other roles, community pharmacists have played a huge role in vaccination schemes, by promoting and offering COVID-19 vaccine doses alongside counselling to patients on how to overcome symptoms caused by these vaccines¹⁷. Overall, the pandemic has allowed societies to understand the significance of pharmacies, particularly community pharmacies, as it has given the opportunity for communities to interact more with their local pharmacies and build a new sense of rapport with them¹²,¹⁷. As a matter of fact, roles of pharmacists vary between countries and states. As a further discussion on the changes of pharmacist roles impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, we have decided to look into the USA as a comparison to the UK⁷. There are substantial differences of the roles of pharmacists in these two countries despite their similar healthcare responsibilities⁷. One such fundamental difference is that unlike in the UK, in many States (such) authority is shared between pharmacists, authorised doctors and in certain States, other authorised medical practitioners⁷. As a result, in the ‘physician dispensing States’, there is a seemingly competitive relationship between doctors and pharmacists for dispensing revenue⁴. Moreover, while the childhood vaccination programme can only be carried out in GP (family physicians) clinics in the UK, as of 2020, pharmacists from the entire USA have been allowed to provide childhood immunisations without prescription, compared with 28 out of 50 States in 2019¹⁷. This essentially means these vaccinations can be carried out in many other healthcare settings¹¹. This would be one of the essential changes to pharmacist roles in the USA due to the COVID-19 pandemic as such permission was given by the federal Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), using public health emergency powers in 2020¹¹. Similarly, pharmacists in the USA had been authorised by the HHS to provide FDA-approved COVID-19 tests for community testing¹, compared with pharmacies in the UK being centres for distribution of lateral flow test kits⁸. By all means we need to recognise the significant contributions of pharmacists in both countries during the pandemic both by providing accessible healthcare services to the general public and by administering COVID-19 vaccines¹³,². Whilst life may be returning to a new normal, there is no denying that the COVID-19 pandemic has left its toll on the global population since its emergence in March 2019. Figures from the Office of National Statistics indicate that cases of depression doubled during the pandemic, with those most affected being the unemployed, women, ethnic minorities, the LGBTQ community and the elderly¹⁴,¹⁵. Whilst recent studies have shown an increase in resilience and coping mechanisms since the third lockdown, some groups have seen deteriorations and sustained distress. With the community pharmacist having the most access to the general public than any other healthcare professional, they have played a large role in facilitating the gap in mental health services to help the public process the consequences of their isolation, grief and economic status¹⁴. One of the ways in which this is currently being targeted is through increased vigilance and rapport with the public to identify early signs of mental health issues such as social withdrawal, mood changes and confusion or difficulty concentrating, which are common symptoms in mental health disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, generalised anxiety disorder and bipolar disorder¹⁴. Community pharmacists also increased monitoring of repeated OTC requests particularly that of analgesics, antihistamines or herbal remedies like St John’s Wort, which indicate self-medicating to relieve pain and reduce anxiety respectively¹⁴,³. They also focused on their ability to empathise, refer and sign-post to the GP, specialist mental health services or local support groups, particularly when speaking to a patient who had recently been bereaved or was relapsing or experiencing the worsening of symptoms¹⁴. The footprint left by pharmacists as a key part of the solution, providing essential healthcare services during the time when they were most needed, will not be forgotten. With the increase in recognition of the role of the Pharmacist during the pandemic and its aftermath, the trust for the pharmacist can only grow as individuals can begin to appreciate their unique clinical knowledge and accessibility to information, advice and services, whether it be COVID-19 related or not. Authors: Alex Ho, Anika Chamba, Samia Hoque and Sara Bashiri References

|

�

Categories

All

Archives

October 2022

|