|

There are lots of ways to study, some highly effective, others less so. The book How We Learn advocates spacing out study sessions, whereby the same topic is focused on for a short period of time spanned over a few days.¹ It might feel like a bit of a challenge at the beginning, but by gradually re-acquiring knowledge through flashcards and self quizzes one’s learning can become long-lasting.² We have put together the UCL Weebly Blog team’s own accounts of our study methods in this entry. We have covered some ways that have proven to be effective in our studies, such as the Pomodoro time management technique, recording oneself reading aloud lecture notes, actively recalling by answering self-test questions and understanding the context of assignments to actively engage with the learning. We hope this entry can be helpful with your studies, especially as the exam seasons are coming up and we wish you all the best of luck!

I’m Samia: a first-year student in the MPharm degree. As someone who is at the start of my university life, I’ve had to adapt to the various forms of learning that have been exposed to me since starting. One significant change is the structure (or rather, lack of) at university; rather than having a set routine to follow each day, the timetable is constantly changing, meaning that I need to be able to mould my study methods around the different lab classes and workshops that I need to attend. Firstly, before I begin studying - it is important for me to set out my intentions for the day - this could be in the form of a simple to-do list or a more comprehensive schedule. Personally, I like to create a daily time-blocked schedule: this allows me to understand exactly what tasks I need to complete whilst also allowing me to schedule time for my hobbies. The main way in which I study effectively is by constantly implementing the concept of active recall when learning a new concept. Rather than making countless notes, my learning process involves three simple steps - understand, question and recall. Initially, I prioritise trying to completely understand a topic - by engaging with a lecture through annotating the lecture notes - as I go along the lecture slides, I create concise recall questions. Once I have finished studying a topic, I answer the recall questions - thus allowing myself to actively recall whilst also being able to immediately identify the gaps in my knowledge. Although this is my method of learning, the concept of actively recalling a topic can come in many forms and can be personalised to each individual. Furthermore, managing stress and maintaining a healthy work-life balance is crucial to the process of studying. Although these factors are often forgotten about, not prioritising your mental health can lead to ‘burn-out’ and negative mental health. One way that I maintain a healthy work balance is by ensuring that there is a specified time during the week which is purely dedicated to my hobbies - whether that be reading a new book, visiting a new café or going on a walk. As someone who is susceptible to getting ‘burn-out’ from overworking myself, I also prioritise having a consistent healthy sleep schedule, by creating an evening routine - this routine allows me to spend the last few hours of my day in a state of calm by relaxing and therefore, recharging myself for the next day. Overall, I have established that having a study schedule is as vital as maintaining a good balance between study and life, thus allowing a student to prosper whilst being in a positive state of mind. I’m Alex and I’m currently in the second year of the MPharm degree. Learning in the second year involves understanding the fundamental scientific knowledge that underlies common diseases and its application. This application of knowledge is delivered through the chemistry and pharmacy practice modules. My process of learning is to skim through lectures during term time, because most of the time I would be busy dealing with coursework, assignments, laboratory classes and extra-curricular activities; then during the breaks is when I can devote most of the time drilling into topics. One way I find which helps in understanding the factual topics is to read the lecture notes aloud and record myself. It is with reading out loud and involving the two senses of sight and hearing, that I can actively recall what I have learnt from lectures and fill any gaps in my knowledge. Recording myself may seem silly, but it does serve one essential purpose, which is to conveniently pack what I learnt into an easily accessible form. For practical topics, making mistakes is key for me. I allow myself to make mistakes as it helps me to identify my logical flaws and fix any misunderstandings I have about the topics. I am constantly aware of the time involved in this entire learning process and I must admit that I am more than frequently burnt out. I have tried various time management methods but most of them did not work for me. One method which suits me well is to exercise and have entertainment before studying or revising. I then find myself in the mood for studying! I’m Anika, a third year student in the MPharm degree. Being a third year, the most important thing is to be aware of deadlines and managing time efficiently. Not only is this crucial during term time but it is also crucial during the exam season. When preparing for your exams, have a clear structure of what you need to get done. Break this down very clearly into weekly and daily activities to ensure you go through all the material in manageable bitesize chunks. Be as realistic as possible with your daily tasks. I cannot stress this enough - none of us are robots or instant-energy-machines - we cannot possibly focus for a full 24 hours, so be kind. Prioritise the content you struggle with most and more importantly, allocate breaks. One way to do this is through the Pomodoro technique - work for 30 minutes, have a break for 5 minutes, and repeat. Try to get into a good routine, waking up, starting work, having lunch and sleeping at particular times. This helps to motivate and programme your brain to associate certain times of day with particular activities in order to build them into habit. There may be days when you want to sleep in or you struggle to work and that is okay, because whilst it is important to study smart and implement good habits, at the same time it is equally, if not more important to look after yourself as we near exam season. Dedicate time for yourself and build this into your work schedule, whether that be 30 to 60 minutes, or longer, of re-watching your favourite TV series, meeting your friends or continuing that creative project you’ve been meaning to. It is essential, for your wellbeing and to prevent burnout, to focus completely on something you enjoy, besides work. Hope that helps! I’m Sara, and I am currently in my fourth and final year of the MPharm degree. If there was one tip I could share it would be to never give up and to always aim to be your best self, no matter which stage of the course you are at. I noticed that particularly in Year 3, paying attention to the lecturer’s advice and then thinking about what I really wanted to achieve from each assignment helped to put me on the right track. The main difference between fourth year and the previous years of the programme is that this year we are expected to work on most coursework on our own and to use our fundamental knowledge to integrate the different disciplines within pharmacy. We also had the entire Term 1 to spend on our Masters’ research project, so taking responsibility for our work, planning and time management were key. At times, I almost regretted choosing a specific topic for my pharmacology project and some days, identifying the ‘‘right’’ studies and statistical tests to include in the meta-analysis seemed like an insurmountable challenge. However, by asking my supervisor and peers for help and also looking up the concepts or tests I was unsure about allowed me to put everything into context and to exclude information that was likely to confuse the reader. We had experience of writing essays to critically analyse a topic as well as creating and presenting posters mainly from Year 3, so it has been less difficult to approach such tasks for the MPharm research project. On a final note, especially in Years 3 and 4, I suggest that you start early, try and gather as much feedback as you can, take regular breaks, create a rough plan or to-do list daily and/or weekly and lastly, enjoy your time at pharmacy school by joining clubs or societies. That’s all from us! We hope this was useful for you and that you have learnt a thing or two. Exam season is tough but you have gotten this far with your studies so we have no doubt you can get through all your upcoming hurdles too. If you have any study techniques we missed that you’d like to share, then message or tag us at @uclpa on instagram. All the best with your studies! Authors: Alex Ho, Anika Chamba, Samia Hoque and Sara Bashiri. Works Cited:

1 Comment

With COVID-19 leaving the world in disarray, the role of the Community and Hospital Pharmacist has grown and adapted vastly to meet the growing physical and emotional needs of the global population, particularly within the healthcare systems of the United Kingdom and United States. By bridging the gap in mental health, providing additional services like COVID-19 vaccinations and screening and sign-posting patients to name only a few services, the Community Pharmacist has been able to serve an integral role of support to the nation, taking the strain off other healthcare professions and providing a key means of accessibility to clinical expertise and advice. It is of utmost importance to note that pharmacists across the globe effortlessly continue to directly care for patients and take on frontline responsibilities amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, yet they are often overlooked when other healthcare professionals are proclaimed⁵. Community pharmacists have effectively reduced the strain on the healthcare system by triaging and screening patients, thus re-routing them away from hospitals⁵. In addition, they respond quickly in other ways to such public health issues, for instance by issuing guidance on professional practice, maintaining the medicines supply chain, handling drug shortages, facilitating the remote provision of pharmacy services, warning against self-medication, taking part in clinical trials and educating on the proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE)⁹. Pharmacists across different sectors have adopted rather different roles during this phase of enormous burden on the healthcare system and resource limitations⁵. Especially in low to middle income regions, community pharmacists provide essential services for free, including ensuring access to telehealth services, dispelling misconceptions and running minor ailments consultations⁵. Hospital pharmacists, on the other hand, evaluate COVID-19 protocols through their presence in ward rounds and antimicrobial stewardship schemes, and also by interpretation of test results and identifying new drug therapies⁵. We have learnt from ‘specialty pharmacists’ how to provide the optimal level of coordination and care to patients remotely, given that they have a long track record of treating patients holistically, and feedback has been remarkably positive from both patients and staff ⁶,¹⁷. Within the UK, a sector of pharmacy which has seen some significant changes is the community pharmacy. Although the ‘pharmacy first’ message has been emphasised and continuously promoted for years, the COVID-19 crisis has led to more patients coming into the pharmacy to treat minor illnesses¹⁷. Additionally, for the majority of patients, the pharmacy acted as their first point of contact, with other healthcare providers, such as GPs being difficult to access, so community pharmacies were presented with more patients, with a wider range of problems¹². Despite the stress that coronavirus has inflicted on society, it has led to pharmacies being more interconnected with other healthcare providers, particularly GPs. Community pharmacists are not only responsible for offering advice and providing treatment, rather they have been adopting a ‘gatekeeper’ role, where they can now cater to a wider variety of patients and refer directly into secondary care¹⁷. Finally, alongside their other roles, community pharmacists have played a huge role in vaccination schemes, by promoting and offering COVID-19 vaccine doses alongside counselling to patients on how to overcome symptoms caused by these vaccines¹⁷. Overall, the pandemic has allowed societies to understand the significance of pharmacies, particularly community pharmacies, as it has given the opportunity for communities to interact more with their local pharmacies and build a new sense of rapport with them¹²,¹⁷. As a matter of fact, roles of pharmacists vary between countries and states. As a further discussion on the changes of pharmacist roles impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, we have decided to look into the USA as a comparison to the UK⁷. There are substantial differences of the roles of pharmacists in these two countries despite their similar healthcare responsibilities⁷. One such fundamental difference is that unlike in the UK, in many States (such) authority is shared between pharmacists, authorised doctors and in certain States, other authorised medical practitioners⁷. As a result, in the ‘physician dispensing States’, there is a seemingly competitive relationship between doctors and pharmacists for dispensing revenue⁴. Moreover, while the childhood vaccination programme can only be carried out in GP (family physicians) clinics in the UK, as of 2020, pharmacists from the entire USA have been allowed to provide childhood immunisations without prescription, compared with 28 out of 50 States in 2019¹⁷. This essentially means these vaccinations can be carried out in many other healthcare settings¹¹. This would be one of the essential changes to pharmacist roles in the USA due to the COVID-19 pandemic as such permission was given by the federal Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), using public health emergency powers in 2020¹¹. Similarly, pharmacists in the USA had been authorised by the HHS to provide FDA-approved COVID-19 tests for community testing¹, compared with pharmacies in the UK being centres for distribution of lateral flow test kits⁸. By all means we need to recognise the significant contributions of pharmacists in both countries during the pandemic both by providing accessible healthcare services to the general public and by administering COVID-19 vaccines¹³,². Whilst life may be returning to a new normal, there is no denying that the COVID-19 pandemic has left its toll on the global population since its emergence in March 2019. Figures from the Office of National Statistics indicate that cases of depression doubled during the pandemic, with those most affected being the unemployed, women, ethnic minorities, the LGBTQ community and the elderly¹⁴,¹⁵. Whilst recent studies have shown an increase in resilience and coping mechanisms since the third lockdown, some groups have seen deteriorations and sustained distress. With the community pharmacist having the most access to the general public than any other healthcare professional, they have played a large role in facilitating the gap in mental health services to help the public process the consequences of their isolation, grief and economic status¹⁴. One of the ways in which this is currently being targeted is through increased vigilance and rapport with the public to identify early signs of mental health issues such as social withdrawal, mood changes and confusion or difficulty concentrating, which are common symptoms in mental health disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, generalised anxiety disorder and bipolar disorder¹⁴. Community pharmacists also increased monitoring of repeated OTC requests particularly that of analgesics, antihistamines or herbal remedies like St John’s Wort, which indicate self-medicating to relieve pain and reduce anxiety respectively¹⁴,³. They also focused on their ability to empathise, refer and sign-post to the GP, specialist mental health services or local support groups, particularly when speaking to a patient who had recently been bereaved or was relapsing or experiencing the worsening of symptoms¹⁴. The footprint left by pharmacists as a key part of the solution, providing essential healthcare services during the time when they were most needed, will not be forgotten. With the increase in recognition of the role of the Pharmacist during the pandemic and its aftermath, the trust for the pharmacist can only grow as individuals can begin to appreciate their unique clinical knowledge and accessibility to information, advice and services, whether it be COVID-19 related or not. Authors: Alex Ho, Anika Chamba, Samia Hoque and Sara Bashiri References

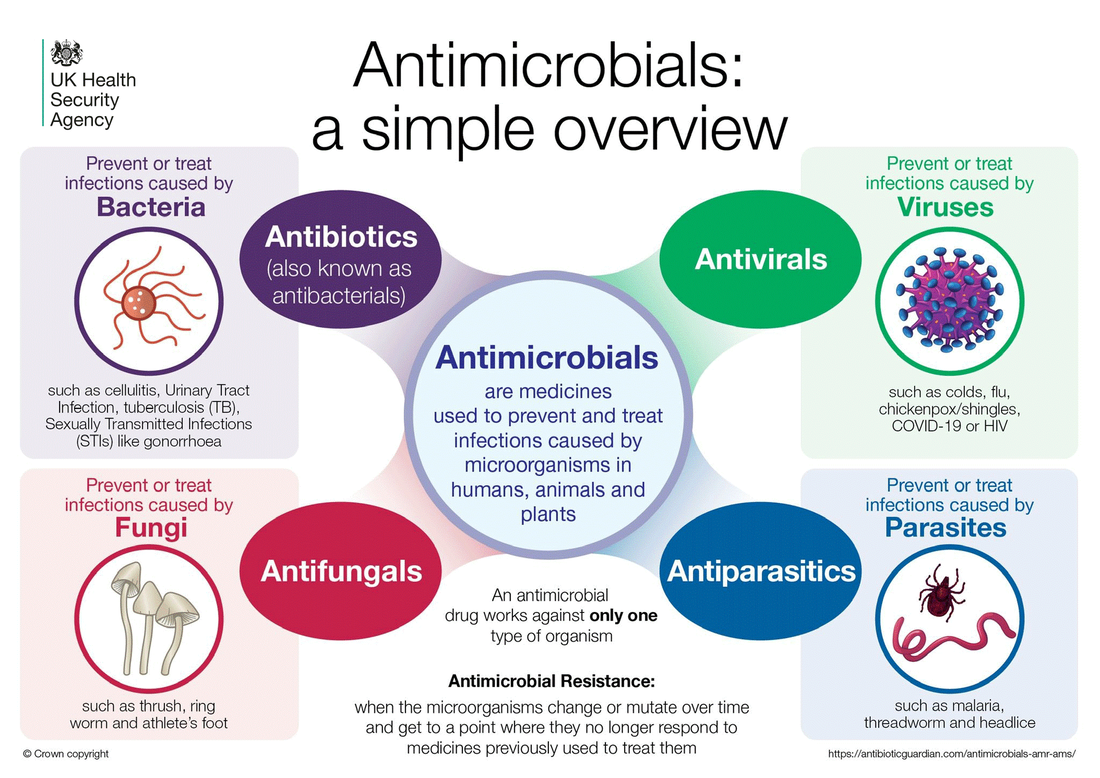

Dr. Diane Ashiru-Oredope In December 2021, the UCL PharmAlliance Medication Safety team were fortunate enough to meet with Dr. Diane Ashiru-Oredope - Pharmacist Lead for Antimicrobial Resistance and Stewardship and Healthcare Associated Infections (HCAI) at the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) and Global AMR Lead for the Commonwealth Pharmacists Association. The Medication Safety team collaborated with the UCL Fight the Fakes team to prepare questions which were then posed to Dr. Diane Ashiru-Oredope. It was a truly insightful and inspiring interview, which covered numerous topics - from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on antimicrobial resistance, to her day-to-day role. 1. Why is antimicrobial resistance a global health issue? The World Health Organization (WHO) declared antimicrobial resistance (AMR) as one of the top 10 global public health threats against humanity, making it a major global health issue. AMR is concerning due to the speed at which it can spread, which is accelerated because of open borders, with people travelling often for business or leisure reasons, as well as the fact that it is possible for resistance to spread between humans (and note that as we see now with SARS-Cov-2 virus, healthy people can carry resistant bacteria and pass it on to others). Transmission of resistance from animals to humans can also occur.

High rates of resistance against antibiotics frequently used to treat common infections have been observed worldwide. For example, the rate of resistance to ciprofloxacin, an antibiotic commonly used to treat urinary tract infections, varied from 8.4% to 92.9% in countries reporting to the Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS). There are also high rates of drug resistance reported for fungi, viruses and parasites globally. A report released in 2016 predicted that AMR could cause 10 million deaths each year by 2050 if adequate action is not taken. Inaction can also cause a significant economic burden, as it is estimated that AMR could cost 100 trillion dollars (also by 2050) if it is not controlled. Challenges in tackling AMR include lack of sanitation and clean water in some areas of the world, which can cause increased instances of microbial infections. The misuse and overuse of antimicrobials to treat infections are also important drivers of AMR, as it allows mechanisms of resistance to spread more easily. There is also a limited pipeline of new antimicrobials, with the last discovery of a new class of antimicrobials being more than 30 years ago. Antimicrobials being developed today are combinations of existing classes. In 2020, WHO revealed that “none of the 43 antibiotics that are currently in clinical development sufficiently address the problem of drug resistance in the world’s most dangerous bacteria”. In addition, highly resistant infections called ‘superbugs’ are on the rise, a common one being methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). These infections are resistant to several types of antimicrobials, making them even more difficult to treat. In relation to the pandemic we are currently facing, the COVID-19 pandemic has shown us a real-life experience of what infections can do when untreatable. 2. Has the COVID-19 pandemic affected antimicrobial resistance in any way (both positively and negatively)? In England, there is the English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilisation and Resistance (ESPAUR) - an annual report which includes data on antibiotic prescribing and resistance, as well as antimicrobial stewardship. The ESPAUR report 2021 (data to end-2020) showed that the overall incidence of infection dropped between 2019 and 2020. This can be attributed to the fact that people stayed at home more often during this time and measures such as social distancing and masks were in place, making infections less likely to spread. There were also lower rates of antimicrobial prescribing. In contrast, the proportion of bloodstream infections resistant to one or more antibiotics has increased, suggesting we are likely to see a rise in antibiotic-resistant infections as pandemic-related restrictions are discontinued. People are mixing more now in England and many places have opened up, so we have to be alert and continue to exercise caution. There have been challenges in maintaining many antimicrobial stewardship activities including audits and quality improvement activities, especially in hospitals, where resource has been allocated to dealing with the acute impact of COVID-19. However, in a recent survey of infection pharmacists, some positive impacts were noted, including the use of technology to support meetings, for example virtual ward rounds have become possible, as well as the acceptance of biomarker tests (e.g., procalcitonin). We are also seeing primary care general practitioners (GPs) continue to access and utilise antimicrobial stewardship resources. 3. What has the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) implemented to tackle antimicrobial resistance? The UKHSA is proactive in implementing the UK AMR strategy and leads on national surveillance of antimicrobial resistance, prescribing, and stewardship in England. The ESPAUR report is published annually. The UKHSA also highlight key behavioural change strategies and leads on public awareness campaigns such as Keep Antibiotics Working. We work in partnership with NHS England and NHS Improvement and other government organisations to tackle antimicrobial resistance. There are also several Antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) activities that we lead on in the form of education and training opportunities for healthcare professionals (HCPs) and the public. For example, the Antibiotic Guardian campaign, where people can pledge to make better use of antibiotics to help tackle antimicrobial resistance. We currently have more than 147,000 pledges in more than 80 countries. It is a global support system. Antimicrobial stewardship for primary and secondary care is also provided by the UKHSA, examples of which are the TARGET Antibiotics toolkit for primary care and the ‘Treating Your Infection Respiratory Tract Infection (TYI-RTI)’ which includes information leaflets for patients. The latter is available in more than 20 languages so more people can benefit. These resources are also free of charge. There are also online interactive and fun teaching materials on infections and AMR resistance and stewardship through the eBug website for educating children and young people, and the Antibiotic Guardian platform runs a ‘schools ambassadors’ campaign. Professionals in public health and healthcare provide teaching sessions in local schools around tackling AMR – largely supported by the excellent eBug materials. The UKHSA leads World Antimicrobial Resistance Awareness Week for England, a campaign to raise awareness of AMR. The week runs from 18-24 November each year and this year focused on disseminating digital resources, including digital ‘sticky notes’, teleconference backgrounds, screensavers and promoting social media activity, including Twitter polls and videos from senior leads in partner organisations, pledging their ongoing support of tackling AMR. Lastly, we publish data on AMR openly, and to my knowledge I believe England is still the only country which does so to a locality level (GP practice, CCG, hospital). The data published includes AMR and antibiotic prescribing data for Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs). 4. Can you tell us a bit more about your research/day to day work? I have two roles, my main role is as the Lead Pharmacist for Antimicrobial Resistance, Stewardship and healthcare associated infections (HCAI) at UKHSA, I also have a role as the Global AMR lead for the Commonwealth Pharmacist Association (CPA). I am also an honorary lecturer at the UCL School of Pharmacy, and I am currently leading a UK wide evidence review on pharmaceutical public health on behalf of the 4 UK Chief Pharmaceutical Officers. I focus most of my time on AMS projects at UKHSA, such as developing a new stewardship workstream to consider surveillance for COVID-19 antivirals. I am also currently focused on developing the strategy and planning for the coming year, commenting and providing feedback on a range of documents including policy, guidance and Patient Group Directions (PGDs). It can be challenging but it is actually really fun, rewarding and I love my role. For my global AMR role, this week I have been on teleconferences with colleagues in Sierra Leone, Nigeria, Uganda and other African countries, to support AMS initiatives to tackle AMR. I have also been focused on the UK-wide pharmaceutical public health research, by drafting the final report and writing a presentation to the Chief Pharmaceutical Officer for England (Prof Keith Ridge) and the Pharmacy Advisory Group (PAG). Something else that I do is support and mentor trainee pharmacists as a General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) report found that Black trainee pharmacists perform less well in the registration assessments. This week I have discussed clinical academic career pathways for pharmacists and met with colleagues at Imperial College London to collaborate on a Patient and Public Engagement Strategy on AMR and health inequalities. I've also had discussions around advanced clinical practice in public health for healthcare professionals, as well as meetings on AMR campaigns. I also lecture/contribute to sessions at universities such as Schools of Pharmacies at UCL and Aston University. At Aston University, over the last few weeks I have been supporting one of their elective modules on AMR. 5. Out of the many global health issues, why was it important for you to focus on antimicrobial resistance? My journey with antimicrobial resistance started when I was an AMR pharmacist in hospital, after which I got a role in the Health Protection Agency as it was then. AMR became more than a day job for me when I watched a documentary about an 11-year-old girl who got a simple scratch. She started to complain about hip pain, and soon after was admitted to hospital. She did not come out until 5 months later, and when she did, she was in a wheelchair, blind in one eye and had survived double lung transplants due to an untreatable infection. What had happened was that resistant organisms had caused an infection, and the doctors could not treat this infection, which meant the infection wreaked havoc on her body. I watched another documentary where another child had cut the cuticle of their finger, and due to a resistant infection, ended up having to have their finger cut off. At the time my children were very young, and I thought to myself this could happen to anyone, and realised AMR was something I wanted to help address. I wanted to do more to raise awareness and increase public engagement. One of the main things I focused on was the development of what is now called the Antibiotic Guardian campaign, as well as join the CPA, to support and learn from the CPA and other organisations as well as colleagues in other countries. 6. How do falsified and substandard medicines contribute to antimicrobial resistance? The WHO in 2017 released a report on the burden of substandard and falsified Antimicrobials where their global analysis highlighted that 11% of antimicrobials contained subtherapeutic concentrations of active ingredient. Of course, these will not adequately treat an infection. This can lead to an increase in antimicrobial resistance. It is bad enough that we have effective medicines for which resistance develops, falsified and substandard antimicrobials pose an even greater risk of resistance developing and spreading. If infections cannot be treated adequately, it will lead to increased mortality rates, an increase in morbidity and increased risk of resistance spreading to other people. 7. What measures can be put in place in pharmacy practice to ensure the impact of antimicrobial resistance is reduced? Infection prevention and control - pharmacy practice can put measures in place to prevent infections happening in the first place, reduce the risk of resistant organisms developing and reduce the need to use antimicrobials. Vaccination reduces the burden of infection, and so can reduce the risk of AMR, so pharmacies can provide vaccination services and/or promote vaccination We can also optimise the use of antimicrobials. For example, if a patient presents with a self-limiting infection, we can give support without suggesting antimicrobials. Like I said before, there are resources such as the TARGET Antibiotics toolkit for primary care and the ‘Treating Your Infection Respiratory Tract Infection (TYI-RTI)’ which includes information leaflets for patients. We can inform patients how long infections will last for, when to worry or talk to a HCP, basically safety netting and giving self-care advice. When patients come in with prescriptions, pharmacists should assess prescriptions for appropriateness and provide adequate counselling. The Pharmacy Antibiotic Checklist is a useful resource. We can assess how we are doing in terms of supporting tackling AMR by conducting audits and quality improvement projects. Finally, we have a key role in raising awareness of AMR to the public and educating other healthcare professionals. 8. What can university students and student organisations such as PharmAlliance and Fight the Fakes do to raise awareness on antimicrobial resistance? What you are doing right now. Educating yourselves on this important global health issue and engaging in discussions around AMR. Public engagement is another way to raise awareness on antimicrobial resistance - university students have a key role in lobbying within their university, for example through leading campaigns during World Antimicrobial Awareness Week. Students can also start simply with talking to family and friends, educating them on AMR and what we can do as individuals to mitigate its impact. Students can also organise activities such as workshops to ensure the engagement of their peers in tackling AMR. Some examples are Vaccination Champion and Antibiotic Guardian. You can also raise awareness of AMR by posting on social media. Using the hashtags #AntibioticGuardian and #KeepAntibioticsWorking is encouraged, as we can see what excellent awareness activity you are engaging in throughout the year. I hope one day I may work alongside some of your readers in taking the fight forward together. For more information on antimicrobial resistance, we recommend you watch this video explainer where Dr Diane Ashiru-Oredope explains what role microbes have on our planet, how antimicrobials work, what the origins of antimicrobial resistance are and more importantly, what can you do to help reduce it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MENdrA8B0N4 Authors: Dorothea Tang, Nusayba Ali and Janice Wong Acknowledgments: Yasna Nasrollahi and UCL Fight the Fakes Addiction and health Substance use disorder (SUD), commonly referred to as ‘addiction’, can be perceived as ‘taboo’ and surrounded by stigma. But the fact of the matter is, SUD is complex and there are so many forms it can take — a single blog would not do the topic justice. As pharmacy students and future pharmacists, it is likely that we will meet patients with SUD, so it is of paramount importance that we have knowledge of the condition. This blog will focus on SUD in relation to the following substances: opioids, alcohol and tobacco. Substance use disorder The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V) — the handbook used by health care professionals in the United States and around the world as the authoritative guide for the diagnosis of mental disorders — describes SUDs as a part of a class of disorders known as substance-related disorders. Substance-related disorders include 10 separate classes of drugs, 9 of which have been attributed to SUD.¹,² The British Medical Association (BMA) defines SUD as the repeated use of a psychoactive substance/s, such that the user tends to be periodically or chronically intoxicated, displays a compulsion to take the substance/s and finds it extremely difficult to cease taking the substance/s; demonstrating a determination to acquire the psychoactive substance/s by ‘almost any means’.³ Substance use disorder can often stem from drug misuse, whether intentional or unintentional.³ Drug misuse is the ‘use of a substance for a purpose that is not consistent with legal or medical guidelines’.³ In other words, the use of a drug that goes against medical advice or the law. The term ‘drug use’ is sometimes used instead of ‘drug misuse’ by healthcare professionals as it is perceived to be less judgmental and will be the term used in this blog.³ SUD related to drug use is the compulsive need to take a drug that can be difficult to control, despite the person being aware of the negative consequences of its usage.⁴ When a person takes a psychoactive drug, the reward circuit of the brain releases dopamine and produces feelings of elation.⁴ The dopamine release reinforces the feelings of pleasure, which gives the drug the ability to be addictive.⁴ SUD can even be initiated by as-prescribed use of a drug, as repeated drug use can change the brain’s biochemistry such that the brain’s ability to resist compulsion for the drug is challenged, resulting in a harsh cycle of recovery and relapse.⁴ The impact of drugs use is significant. It has been associated with poor physical and mental health, as well as death, unemployment, homelessness, family breakdown and criminal activity.⁵ In fact, drug use is the third most common cause of death for those aged 15 to 49 in England.⁵ This reveals the pressing need to help people quit drug use in an effort to improve and preserve the lives of these individuals and better society as a whole. Opioid use disorder Opioid use disorder (OUD), also known as ‘opioid dependence’ is defined in the DSM-V as “…a problematic pattern of opioid use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress…”² A joint paper by the World Health Organization (WHO), The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the United Nations AIDS division (UNAIDS) states that: ‘substitution maintenance therapy is one of the most effective treatment options for opioid dependence.’⁷ The type of substitution maintenance therapy can vary between countries and even between patients. In the United Kingdom (UK), The Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) supports methadone treatment as a maintenance treatment to recover from and overcome OUD, stating that methadone is ‘not a cure for addiction’ but is a ‘safer alternative’ to the use of illicit opioids such as heroin.⁸ However, the RPS recognises the limits of methadone treatment in the long-term, and so supports a holistic approach where methadone or newer therapies such as buprenorphine are combined with other interventions such as psychosocial interventions to help drug users recover from OUD.⁸ In the United States (US), OUD has been linked to the misuse of prescription opioids.⁶ In fact, in 2016, 11.5 million Americans self-reported that they had personally misused prescription opioids in the previous year.⁶ Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is considered the Gold Standard treatment option for OUD in the US.⁶ MAT for OUD is the use of one of three medications, namely buprenorphine, naltrexone, or methadone in combination with psychosocial and/or behavioural therapy.⁶ OUD is also a concern in Australia, with heroin the 4th most common principal drug of concern in 2016–17.⁹ One of the main treatment types used for OUD in Australia is opioid pharmacotherapy which involves regular use of a legally obtained, longer-lasting opioid, examples of which are methadone, buprenorphine or buprenorphine-naloxone.⁹ Tobacco use disorder When we think of the long-term effects of smoking tobacco, people may immediately jump to lung cancer as the major condition- and they aren’t wrong. Smoking is the cause of 7 out of 10 lung cancer cases, and it can also cause or worsen other lung conditions like asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).¹⁰ But what many people don’t realise is that it can cause a whole array of other conditions, including many cancers like liver and pancreatic cancer, and also increase the risks of heart attack and stroke in otherwise healthy individuals.¹⁰ Smoking causes around 100,000 deaths in the UK alone each year.¹⁰ With these facts in mind, it’s understandable that 50% of smokers try to quit each year.¹¹ Despite this, only 6% of smokers manage to quit smoking in a given year.¹¹ When a person smokes a cigarette, nicotine binds to cholinergic receptors to release dopamine, causing an elated sensation while reducing stress.¹¹,¹² Over time, the receptors become desensitised and nicotine levels in the body decline, causing the person to feel withdrawal symptoms like irritability and anxiety.¹¹,¹² These symptoms, alongside other factors like environmental stressors and smoking cues, add to the craving urges the person experiences to continue smoking.¹² Although the number of smokers continue to drop annually due to the decreasing appeal of smoking and improvements in health education, there is still a substantial subset that smokes regularly (14% for the UK in 2019).¹³ As future pharmacists, we will be in a position to help people quit smoking and lower the number of people with tobacco use disorder further. Smoking cessation programmes are offered by some pharmacies in the UK. One key service is the promotion of nicotine replacement therapy, where nicotine formulations like patches and gums are offered to patients in the event that they are considering or trying to quit. In addition, an important campaign that pharmacies promote in the UK is Stoptober, where smokers are encouraged to quit smoking for 28 days during the month of October.¹³ In 2019, 25% of smokers nationwide attempted the challenge, with 8% continuing to abstain after the four weeks, suggesting that this campaign does have an impact on the smoking population.¹³ In North Carolina the programme QuitlineNC is also available as a free smoking cessation service, which provides 24/7 telephone and online coaching.¹⁴ In Victoria, the programme Quit offers a hotline where smokers can access a trained counsellor to speak to for advice and support, as well as access to regular texts that offer encouragement in their journey.¹⁵ Alcohol use disorder Alcohol is often portrayed by the media as a ‘glamorous’ or an ‘exciting’ thing to have on a night out with friends. It is possible that due to this association, people don’t usually link its consumption with addiction. When people drink alcohol, they tend to feel more fun, confident or relaxed, as alcohol stimulates dopamine release.¹⁶ However, this can also cause people to become psychologically dependent on alcohol, where they feel that they need a drink- this is the basis of alcohol use disorder (AUD), also called ‘alcohol dependence’.¹⁷ Another sign of AUD is worrying about when the next drink will be available and wanting a drink in the morning.¹⁷ This psychological reliance also results in physical dependence where people develop shakes, sweats and feel nauseous and anxious without a drink.¹⁷ Over time, this leads to long term effects like hypertension, heart disease or liver disease, so identifying when a patient needs treatment is essential in helping them avoid these effects.¹⁸ The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test developed by the World Health Organisation is available for people worldwide to use to identify if an intervention is needed, with a score of 8 or more indicating hazardous alcohol use.¹⁹ Many UK pharmacies display educational posters explaining that adults should not drink more than 14 units of alcohol a week, with half a pint of beer being equivalent to 1 unit and a small glass of wine being 1.5 units.²⁰ There are also many leaflets available with the contact details of support groups such as Alcohol Change UK, Alcoholics Anonymous in the US and SMART Recovery in Australia. Patients identified as heavy drinkers are encouraged to cut back by having several alcohol-free days per week, and to set a limited budget per week to spend on drinks.²⁰ If the addiction is severe enough to warrant an intervention by a healthcare professional, inpatient treatment is offered at licensed treatment centres.²¹ Monitored detoxification treatment is given to the patient, after which patients recover in residential treatment centres. This is where they can be put on medication-assisted therapy in order to stay sober and avoid relapsing.²¹ The most common drugs used are disulfiram, which stops the body from metabolising alcohol, acamprosate, which prevents alcohol cravings, and naltrexone, an opioid antagonist, which also prevents cravings.²² Disulfiram, a carbamate derivative, interacts with the acetaldehyde found in alcohol and causes it to build up in the patient’s body if alcohol is consumed, causing them to experience symptoms like nausea and vomiting, sweating and headaches.²² Other drugs which can be used include antipsychotics, where the alcohol use is associated with mental illness, and clonidine, an antihypertensive which helps by reducing the side effects caused in the detoxification process such as hot flashes. Anticonvulsants and beta blockers can also be used off-label in treating alcohol use disorder.²² SUD is difficult to define, and even more difficult to treat. Although drug therapies are available to help treat this condition, these are typically offered in conjunction with other therapies (such as counselling) for a more holistic treatment. Pharmacists and pharmacy teams have a role to play in helping individuals overcome the types of SUD described in this blog, and as pharmacy students, we will come across patients battling this condition - if not now than in the future as qualified pharmacists - and the more informed we are about the condition, the better help we will be. Written by: Nusayba Ali and Amelia Ryan References:

With the Rapid Development of Several COVID-19 Vaccines, is Coronavirus Finally on its Way Out?1/12/2021 As of 11 March 2020, the world has been in the midst of a pandemic. A once meaningless word to many, ‘coronavirus’ has taken the world by storm. In fact, Google revealed last December that ‘coronavirus’ was the top trending search for the UK in 2020. Coronaviruses are a family of viruses that cause infection in humans and animals. The one that led to the pandemic is called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) but is more commonly referred to as simply ‘coronavirus’. When an individual is infected with the virus, they may display mild symptoms or no symptoms at all. Consequently, if the individual displays more severe symptoms and potentially need to be hospitalised, they are said to have coronavirus disease or COVID-19. An insidious infectious disease, the impact of COVID-19 has been catastrophic. Since the beginning of the pandemic, one clear solution to eliminate this disease and aid in the return to normal life has been the development of an effective vaccine. With COVID-19 vaccines having been approved for use in the UK and worldwide, is the pandemic finally over?

Vaccines are chemically weakened or dead forms of a pathogen, whereby a pathogen is a microorganism which results in disease. Once a person is treated with a vaccine i.e. they are vaccinated, their immune system is stimulated. This stimulation leads to destruction of the pathogen and the production of memory cells. This means that if a person was infected with the same pathogen in the future, the body remembers how to fight the pathogen. There are several types of vaccines which exist. The four main types of vaccines are live vaccines, inactivated vaccines, subunit vaccines and nucleic acid-based vaccines. The first type, live vaccines, include commonly administered injections such as MMR and tuberculosis vaccines. As the name suggests, they contain the actual microorganism which causes the disease. However, they don’t make people ill due to attenuation, which is a process whereby the microorganisms are reduced in virulence (capability to cause severe disease). This is possible as vaccine developers only use the mutated strains of the organism that have a lower toxicity. However, as they still contain the actual disease-causing microorganism, they cause the body to produce many antibodies. This results in lifelong immunity against the disease. The second type, inactivated vaccines, are made from dead microorganisms. They are safer compared to the live ones, but a higher dose is often needed as the bacteria and viruses don’t replicate inside the body. This makes them more expensive compared to live vaccines. An example of an inactivated vaccine is the polio vaccine. The third vaccine type are subunit vaccines, such as the hepatitis B vaccine. As the name suggests, they only include the antigen parts of the microorganism, which is the part that stimulates our body’s immune system. The final vaccine type is the nucleic acid vaccine, which contains plasmid DNA or mRNA from the bacteria/virus that codes for the antigens that cause an immune response. These mRNA vaccines are considered safe and very effective, which is why they are increasingly being developed. The current vaccines against COVID-19 encompass the second, third and fourth vaccine types; for example, Sinopharm has produced an inactivated virus vaccine, AstraZeneca/Oxford has produced a subunit vaccine and Pfizer has produced an mRNA vaccine. Currently in the UK, the Pfizer, Moderna (another mRNA vaccine) and AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccines have all been approved for use. A report published by Imperial College London’s Institute of Global Health Innovation (IGHI) and YouGov in November 2020 looks at people’s attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccines across 15 countries, including the UK. This report was based on survey responses from around 13,500 people and gives an insight into behaviours related to COVID-19. 65% of respondents in the UK reported being willing to get vaccinated in 2021 if a COVID-19 vaccine became available to them, which made respondents from the UK the most willing to be vaccinated among the countries surveyed. Overall, of all those surveyed, around half (51%) were willing to get a COVID-19 vaccine in 2021. This also reveals how half of those asked, the other 49%, would be hesitant in getting a COVID-19 vaccine if it was available to them. This is not a new concept when it comes to vaccines; vaccine hesitancy has existed for many years and is in fact a global issue. The World Health Organization (WHO) recently listed vaccine hesitancy as one of their top 10 biggest threats to global health. Vaccine hesitancy is the scientific term for anti-vaccination; it is when people with access to vaccines delay or refuse vaccination. Vaccination is one of the most effective ways of eliminating disease across the world, with a staggering 2 to 3 million deaths prevented by vaccination every year. Nonetheless, vaccine hesitancy has grown in popularity in recent years, fuelled by misconceptions and misinformation. This could have potentially devastating consequences on public health. The biggest concern people have regarding the COVID-19 vaccines is whether they are safe. Many are hesitant to be vaccinated as they feel the vaccine was developed too quickly, with the time taken from initial development to the deployment of the vaccines being approximately a year or less. Thus, people are concerned that long-term studies of the vaccines have not been conducted, and so are afraid of the potential long-term implications of a COVID-19 vaccine. An article published by the COVID Symptom Study addresses this concern. The COVID Symptom Study is the world’s largest ongoing study of COVID-19. The study is based on data provided by over 4 million people globally through the COVID Symptom Study app. It is a non-profit initiative launched by health science company ZOE in collaboration with King’s College London. The article explains that the global health emergency created by the pandemic led to billions of pounds being committed to global COVID-19 vaccine research, as well as tens of thousands of people volunteering for the clinical trials of the vaccine. The level of funding for the vaccine meant that scientists all over the world were working on a vaccine and had the means to do so, making the process of vaccine development much faster. In addition, the large number of volunteers for clinical trials further increased the rate of vaccine development, as it can take many months or years to obtain enough volunteers. Furthermore, the genetic code of SARS-CoV-2 was identified quite quickly relative to the spread of disease (January 2020), so scientists were able to begin working on a vaccine immediately. The vaccines were not developed from scratch, rather they were developed based on existing safe and effective vaccine delivery systems. These were adapted to work against COVID-19. For example, the AstraZeneca/Oxford vaccine had been in development and testing for 15 years, having been previously developed to work against other related coronaviruses that cause SARS and MERS. In addition, compared to the past vaccines can be manufactured at a much quicker rate due to modern technology. It is a culmination of these factors which led to the fast development of COVID-19 vaccines. If faced with vaccine hesitant members of the public, it is important to inform them that the safety precautions, clinical trials and tests for the COVID-19 vaccines were conducted as thoroughly as with any other vaccine. The spread of misinformation is especially worrying now as vulnerable patients who see or hear it may refuse the COVID-19 vaccine, thus endangering their life and the health of those around them. Ensuring we are fully educated about the history and development of this virus and its treatment can be what saves them in the future. Authors: Amelia Ryan and Nusayba Ali References:

In the 1920s, Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin kickstarted a whole new era of medicine. The impact was such that penicillin was used to treat pneumonia in soldiers on the battlefields during World War 2. And yet a century later in 2020, over 12,000 people die in the UK due to antibiotic resistance with the number increasing to over 700,000 worldwide. So how did antibiotics go from a “miracle drug” that could cure illnesses previously feared by physicians, to a source of concern for doctors worldwide? After the discovery of penicillin in 1928, infections which previously resulted in loss of life were now being adequately treated by antimicrobials. Antimicrobials include antibiotics, antivirals and antifungals. They are vital in preventing and treating infections. An infection arises when a pathogen enters your body and begins to multiply, with a pathogen being a microorganism (such as bacteria) that causes disease. Antimicrobial resistance occurs when microorganisms no longer respond to the antimicrobials designed to kill them. When antimicrobials lose efficacy as a result of antimicrobial resistance, people can succumb to any number of infections. It has become increasingly apparent that antimicrobial resistance poses a real threat to mankind. In fact, antimicrobial resistance has recently been reported by the World Health Organization (WHO) as one of their top 10 threats to global health. Antibiotics are an example of antimicrobials which are used very widely. They have applications in hospitals, community, food production and in veterinary production. The problem is that the more often antibiotics are taken, the less effective they are. This is because bacteria replicate very quickly- for example, E. coli undergoes mitosis every 20 minutes. During this process, mutations can occur. In general, the change is inconsequential but sometimes, the mutation can benefit the bacteria and give it characteristics that prevent it from being affected by an antibiotic. This trait is then favored via natural selection and the mutated strain quickly outnumbers the original strain. This means that when more people use antibiotics, different species of bacteria have a greater chance at developing these resistant traits. When doctors and GPs inappropriately prescribe patients with antibiotics for conditions like sore throat and sinusitis, it puts patients who genuinely need antibiotics at greater risk of harm. A study found that in general around 1 in 5 antibiotic prescriptions are issued inappropriately in the UK and considering how around 18 in 1000 inhabitants are prescribed antibiotics annually, one can imagine how great the number of people misusing antibiotics is. Antimicrobial resistance requires urgent attention. If action is not taken to combat this phenomenon, many modern medicines could become obsolete. Overcoming antibiotic resistance has been a priority for WHO since 2015. World Antimicrobial Awareness Week is an organized effort by WHO to increase awareness of antimicrobial resistance globally and to encourage practices among the general public, health workers and policy makers, which will prevent further emergence and spread of antimicrobial resistance. Antibiotic Guardian is another initiative that is being undertaken to slow the spread of antimicrobial resistance, specifically that of antibiotic resistance. It is a campaign that was launched by Public Health England in 2014 and aims to encourage health and social care professionals, students, educators in the human and animal health sector as well as members of the public to take action against the spread of antibiotic resistance. By pledging to become an Antibiotic Guardian, you choose to perform a simple action which protects antibiotics against the threat of antibiotic resistance. We can all do our part to stop antimicrobial resistance from spiraling out of control. Prescribers, such as doctors, should ensure that they are appropriately prescribing antibiotics and other antimicrobials, whilst patients should ensure that they take these medicines correctly and finish the full course of treatment. Good hygiene and infection control practices, particularly in healthcare settings, can also prevent infection and reduce the need for antibiotics in the first place. Immunization such as vaccinations are also very useful in preventing infections, further reducing the need for antimicrobials. These measures could reduce the use of antimicrobials and in turn, their misuse, such that we can avoid a future where people succumb to infections as they would have prior to the 1900s. Authors: Amelia Ryan and Nusayba Ali References:

On to the main part of our trip, meetings. With the help of Dr. Andreia Bruno, we were able to book the “Hercules Room” at Monash University-Parkville Campus. Fully equipped with Zoom capable screens and secret cabinets of food and drinks, student leaders discussed not only different projects but also the sustainability and leadership of PharmAlliance student domain. UNC leaders (Clara Kim, Vraj Patel, Jenny Jin, Ember Lu) and Monash University leaders (Alisha Cloti, Kevin Wu, Brandon Pham) were in attendance, while Ruby Akkad from UCL called in from Toronto due to last minute visa issues.

This was the first time that student leaders were able to meet in person. We realized that the value of this face-to-face communication is vital, as the quality of the conversation was much higher and we were able to accomplish much more action items and structures. Ember and I had created meeting agenda templates beforehand, and each school was in charge of different sections of the meeting. Everyone created agendas before their meeting and came well prepared to host the meeting and guide discussions. The first day was spent mostly discussing PharmAlliance student domain leadership so far. The leaders first drafted a mission statement of PharmAlliance student domain: While aligning with initiatives on the PharmAlliance level at the highest possible extent, collaborate on impactful and challenging pharmacy issues that are common between the US, Australia, and the UK. Then, students discussed about different issues with leadership that came up in effectively leading organizations. Students were able to share their experiences and also give advice on how to overcome obstacles. The next day was spent on discussing the Medication Safety Comic series. We decided on logistics, themes, and different topics we want to be included in the comic series. While discussing all of the topics, we made sure that our end goal was having an element of collaboration in each step. Collaboration sometimes may be inefficient; In fact, there are tasks that could easily be done if it were just done within one campus group. However, the leaders were eager to implement collaborative portions across the project, as that is the main goal of PharmAlliance itself. Also, students and leaders in PharmAlliance truly value the unique international collaboration we are fortunate to be a part of, and wanted to take full advantage. The last day was spent discussion the International Case Competition. Vraj Patel and Brandon Pham led the discussions on assessing what was good versus what could be better compared to last year. At the end of the meeting, the leadership team decided to make create interschool teams - i.e. each team will have students from two different countries! This was an exciting development compared to last year, where teams were composed of students in one school. This was again a decision made with the desire to increase collaboration among students across all three countries. We hope that the International Case Competition becomes a unique opportunity for students to learn about each others’ pharmacy practices. A group of Pharm.D. students received a $10,000 PharmAlliance grant — the first of its kind to be awarded to Pharm.D. students — to support a project promoting medication safety. The project is led by PY3 Clara Kim and PY2 Vraj Patel from the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy. It is co-authored by PY3 Ember Lu from the School and students from University College London and Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. Their initiative aims to promote safe use of the three medications most associated with drug errors — opioids, insulins and anticoagulants — through the creation of a comic series that promotes patient education. The comics will be distributed online through social media and offline as posters and fliers posted in community pharmacies in the U.S., England and Australia. “This project will help patients, including those with low health literacy, understand how to take their medications correctly and acknowledge the importance of adherence, while making it fun in the process,” Kim said. Established in 2015, PharmAlliance is an international partnership between the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy, University College London and Monash University. PharmAlliance has provided support for research initiatives developed by faculty and Ph.D. students from each of the three schools. This is the first PharmAlliance grant to be awarded to Pharm.D. students. Along with Kim, Patel and Lu, the project’s co-authors include Monash University students Alisha Cloti and Emma Hatherley, and University College of London student Ruby Akkad. “The student leaders of all three schools are very excited and thankful to be the first student group to have received this grant,” Kim said. “This is a very important step for the PharmAlliance student domain.” The students will be mentored by faculty at each school: David Steeb, Pharm.D., M.P.H. at UNC-Chapel Hill, Andreia Bruno, Ph.D. at Monash University, and Oksana Pyzik, M.Pharm. at UCL. The grant will allow the students to develop their project beyond the conceptual stage and travel to Melbourne to discuss their project, as well as ways PharmAlliance can support student initiatives and foster connections between students at each of the schools in the future. Original article found here, published on November 13, 2018 at the UNC Eshelman School of Pharmacy homepage: "Fight the Fakes" is a campaign that aims to raise awareness about substandard medications, which is a big threat to public and patient safety. University College of London students and faculty have been prominent in the Fight the Fakes campaign, with students and faculty members representing at local and global meetings to raise awareness and advocacy for this very important cause.

The following editorial was posted on April 2018 on the Lancet Respiratory Medicine. Click here to view the full article. The illegal market in fake medicines is a growing threat and is harming patients the world over—this was the headline of Fight the Fakes, an event at University College London (UCL) on March 16, 2018, which aimed to provoke action on the urgent global issue of falsified and substandard medicines. |

�

Categories

All

Archives

October 2022

|